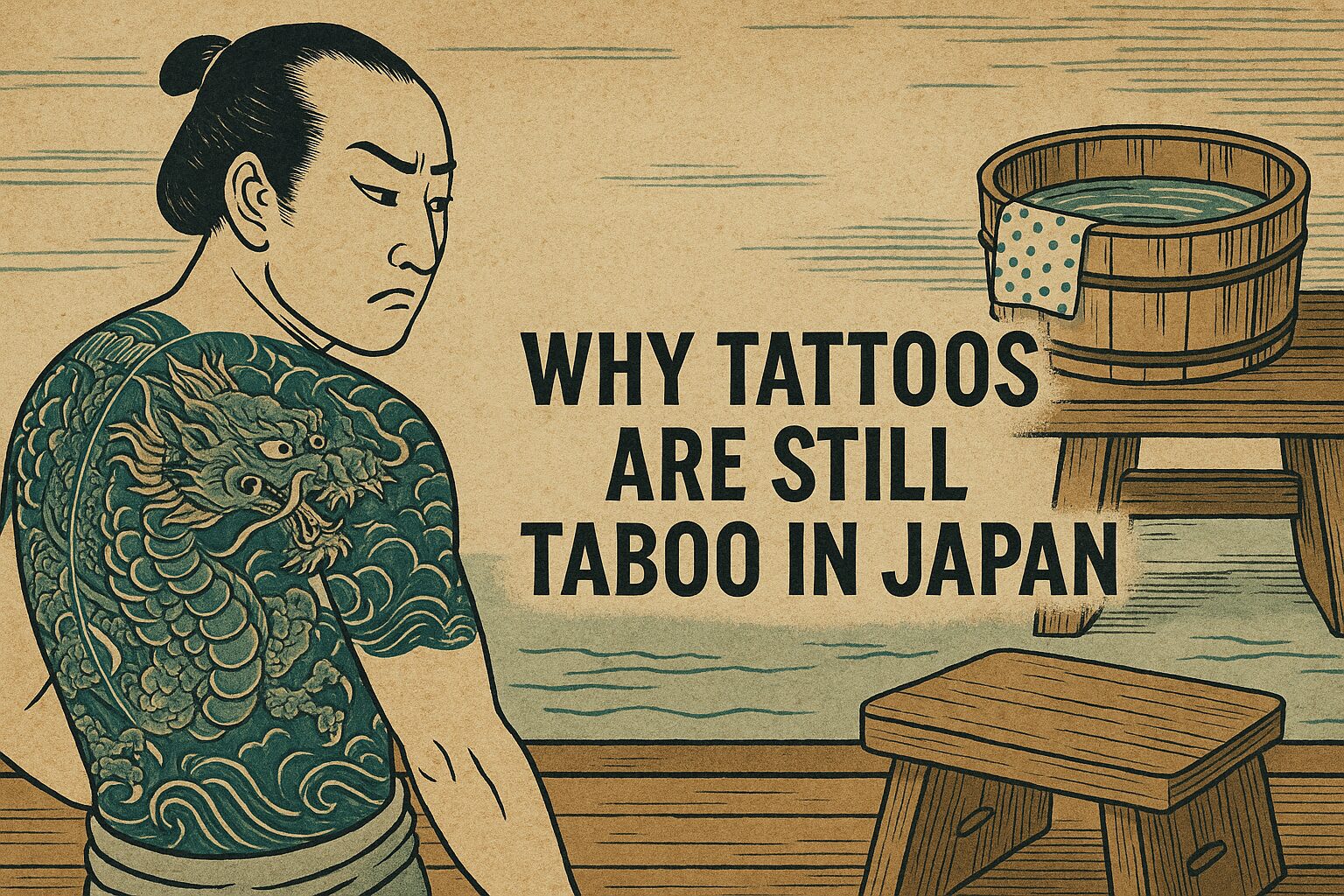

In Japan, tattoos can still trigger puzzled glances—or an outright “no” at hot springs and gyms. Yet that reaction did not appear overnight. Instead, it grew across centuries: first as a penal mark in the Edo period, then as an object of official prohibition under the Meiji government, and finally as a social signal bound up with yakuza imagery in the twentieth century. Today, however, tourism, media, and courts are nudging attitudes, even if change remains uneven across regions and facilities. This guide lays out the key history, clears the most persistent myths, and—crucially—explains what travelers can do in everyday situations. Nippon.com+1

- Quick Answer for Travelers

- Why the Stigma Exists: From Edo Punishments to Meiji Bans

- Ainu Women’s Tattoos and the Meiji Assimilation Policies

- Yakuza Myths, Movies, and Public Morality

- Postwar Shift and the 2020 Supreme Court Ruling

- Onsen, Pools, and Gyms: What Actually Happens Today

- Respectful Tips for Visitors

- FAQ

- Related Guides (internal links)

Quick Answer for Travelers

Tattoos are not illegal in Japan. In September 2020, Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that tattooing itself does not constitute a medical act requiring a physician’s license; therefore, professional tattoo artists do not need to be doctors. Nevertheless, private facilities set their own rules. Most onsen (hot springs) either post “no tattoos,” allow small designs if covered by tattoo cover seals, or provide private/chartered baths (kashikiri) as a workaround. Consequently, the practical playbook is simple: check policies in advance, cover when asked, and choose private options when in doubt. masudafunai.com+2mainichi.jp+2

Why the Stigma Exists: From Edo Punishments to Meiji Bans

First, the historical core. During the Edo period (1603–1868), authorities used irezumi-kei—literally, the “tattoo penalty”—to mark offenders. Although decorative tattoo art also flourished in the same era, the idea that permanent ink could visibly separate someone from the community took deep root. In other words, a tattoo could function as a social scar that followed a person beyond the courtroom. Nippon.com

Second, the newly modernizing Meiji government sought to regulate bodies and public appearance as part of presenting a “civilized” image to Western powers. As a result, in 1872 the state banned decorative tattooing, pushing the practice underground. Crucially, that move linked tattoos with illegality in the public mind and reinforced the association between ink and nonconformity. Even people who admired tattoo art often kept it hidden under clothing, which maintained a public/private split around the body that still shapes attitudes. Nippon.com

Third, though the legal climate changed after the Second World War, culture tends to move slower than statutes. Under the Allied Occupation, the long-standing prohibition was lifted in 1948, which allowed studios to reopen and serve both locals and foreign sailors. Nevertheless, because habits, media, and municipal policies continued to associate tattoos with deviance, stigma persisted in everyday contexts like baths, gyms, and beaches. Discover Japan+1

Ainu Women’s Tattoos and the Meiji Assimilation Policies

However, Japanese tattoo history is not only a story of punishment and prohibition. Long before Meiji-era bans, Ainu women in northern Japan maintained a distinct tradition of mouth and arm tattoos linked to beauty, protection, and rites of passage. As many historians and Ainu cultural organizations note, these were women’s practices with deep spiritual meaning, and they were performed by female tattooists within the community. dajf.org.uk

During the 1870s, the situation changed dramatically. As part of broader assimilation policies, the Hokkaido Development Commission issued measures that banned women’s tattoos (along with men’s earrings and other customs). Documents mention a proclamation in 1871 and subsequent crackdowns by 1876, which rapidly suppressed a living tradition. Because this ban overlapped with the Meiji government’s general prohibition on tattooing, Ainu women’s tattoos declined sharply by the early twentieth century and survived mostly in photographs and oral histories. ff-ainu.or.jp+1

For travelers, this context matters because it shows that tattoo meanings vary widely within Japan’s borders. While Edo’s irezumi-kei fueled stigma, Ainu women’s tattoos signify identity and protection—a reminder that the label “tattoo” covers multiple, sometimes conflicting, cultural logics.

Yakuza Myths, Movies, and Public Morality

From the 1960s onward, mass-produced yakuza films helped cement a visual shorthand: full-body irezumi equaled organized crime, hyper-masculinity, and anti-social bravado. Moreover, municipal regulations and business policies often used this imagery when drafting rules about “anti-social forces,” which, in practice, translated to “no visible tattoos.” Even as many tattooed residents and travelers had nothing to do with crime, the cinematic stereotype bled into daily life—especially in places where people are undressed (baths, pools) or where membership and discipline are emphasized (gyms). J-STAGE

Importantly, this is a myth-plus-policy loop rather than a pure myth. Because facility managers are legally allowed to set dress and conduct codes, private property rules can re-inscribe cultural assumptions long after laws change. Thus a single “no tattoos” sign may reflect risk management, branding, and habit more than a precise moral judgment.

Postwar Shift and the 2020 Supreme Court Ruling

Legally, the picture is clearer today than it was a decade ago. After the 1948 opening, tattooing operated in a gray zone regarding who could perform the act. Some local authorities argued that injecting pigment counted as a medical procedure under the Medical Practitioners’ Law. That view was finally rejected in September 2020, when Japan’s Supreme Court held that tattooing does not constitute a medical act and artists do not need physician licenses. For studios, this ruling was a pivotal confirmation; for travelers, it underscores that tattoos are lawful even if access rules still vary by venue. masudafunai.com+1

Nevertheless, court decisions do not instantly harmonize social norms. Consequently, you may still encounter “no tattoos” policies—especially in conservative or family-oriented facilities—despite the clear legality of body art. This is not unique to Japan; it’s how private governance works worldwide.

Onsen, Pools, and Gyms: What Actually Happens Today

So what should you expect? In practice, policy is not uniform. Some onsen and public baths maintain a blanket ban on visible tattoos, while others quietly accept small designs if covered with tattoo cover seals or skin-tone patches. Many ryokan and hotels offer private baths (kashikiri) or rooms with ensuite onsen tubs, which solve the issue without friction. Moreover, regional tourism offices and the national tourism site increasingly publish “tattoo-friendly” lists or guidance, reflecting inbound demand and gradual normalization. Therefore, the most reliable routine is: check ahead, carry cover options, and default to private baths when you want certainty. Discover Japan

Likewise, pools, water parks, and gyms tend to mirror their brand positioning. Family resorts often prohibit tattoos outright; urban gyms may allow them if concealed; boutique hotels might lean flexible if guests behave discreetly. As always, staff have the final say. A calm, respectful ask—“Are small tattoos okay if I cover them?”—usually gets the clearest answer.

Respectful Tips for Visitors

Because etiquette often matters more than theory, here is a concise, field-tested playbook:

- Ask first; cover when asked. Carry tattoo cover seals or UV sleeves; reapply after long soaks or scrubs.

- Choose private options where available: chartered baths (kashikiri), ensuite tubs, or private family rooms at day spas.

- Dress modestly at shrines/temples. Tattoos are generally tolerated, yet understated clothing in sacred spaces is appreciated.

- Read the room in gyms/pools. If you see a “no tattoos” sign, don’t negotiate; switch to cover or choose another venue.

- Link culture with courtesy. Even when policies feel strict, assume good intent and follow local practice—the visit will go smoother.

FAQ

Are tattoos illegal in Japan?

No. Tattoos are lawful. In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled tattooing is not a medical act requiring doctors, which clarified the legal status of artists. Facility rules, however, remain independent. masudafunai.com+1

When—and why—did Japan ban tattoos?

The Meiji government banned decorative tattooing in 1872 to project a “civilized” image abroad; this pushed the art underground. The ban was effectively lifted in 1948 under the Occupation, yet stigma lingered via custom and media. Nippon.com+1

What about Ainu tattoos?

Ainu women historically wore tattoos around the mouth and on the arms as rites of passage and protection; however, assimilation policies in the 1870s prohibited the practice (with measures noted in 1871 and strengthened by 1876). ff-ainu.or.jp+1

Why do onsen still say “no tattoos”?

Because they are private facilities with brand, safety, or family-oriented considerations. Policies differ, but covering small tattoos or booking private baths often solves the problem. Discover Japan

Is the yakuza link still relevant?

Less than before, but the visual shorthand created by mid-century yakuza movies still influences public perceptions and some policies, especially where people are undressed. J-STAGE

Related Guides (internal links)

- Tattoo Cover Seals in Japan: Where to Buy & How to Use

- Tattoo-Friendly Onsens: What to Expect

- Onsen Etiquette for First-Timers

Notes on dates and terms

- Edo irezumi-kei refers to the formal tattoo penalty used to mark offenders. Nippon.com

- 1872 denotes the Meiji-era prohibition on decorative tattooing; 1948 marks the postwar lifting under Occupation. Nippon.com+1

- Ainu bans are documented as beginning in 1871 with further enforcement by 1876 under the Hokkaidō Development Commission. ff-ainu.or.jp+1

- 2020 Supreme Court affirmed that tattooing is not a medical act—clarifying artists’ legal status. masudafunai.com+1

コメント